|

|

Post by neferetus on Jan 24, 2006 10:22:22 GMT -5

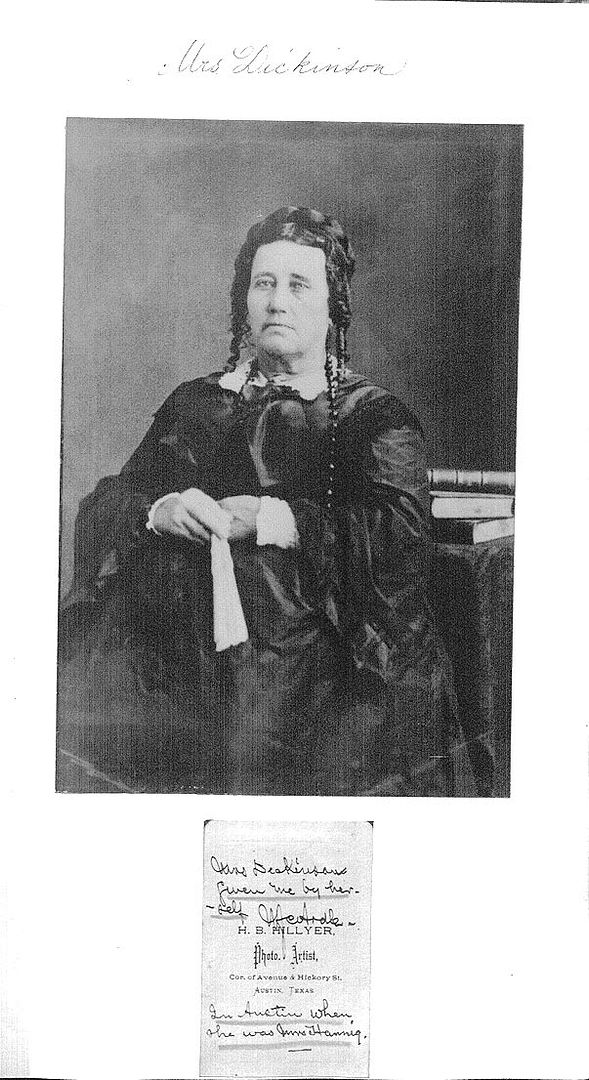

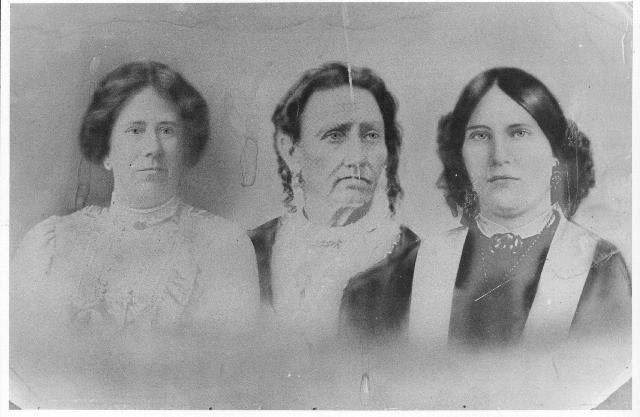

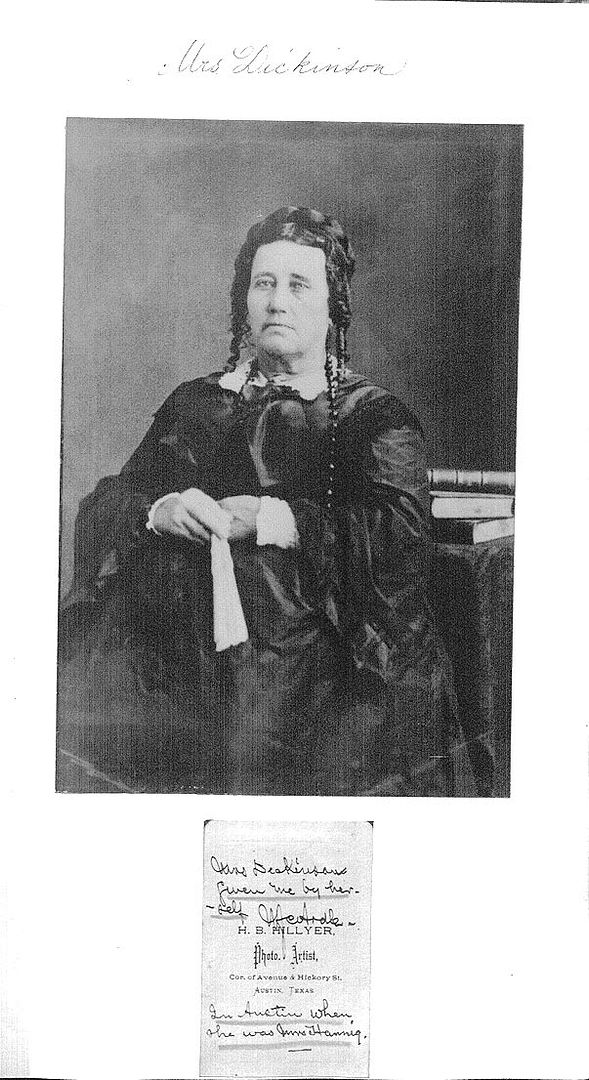

]  Susanna Dickinson,later in life. Susanna Dickinson,later in life.   Susanna Wilkerson Dickinson Hannig and her monument in the Texas State Cemetary, in Austin Susanna Wilkerson Dickinson Hannig and her monument in the Texas State Cemetary, in AustinProbably the most popular of the Alamo noncombatants, Tennessee native Susanna Wilkerson Dickinson, eloped with Almaron Dickinson in 1829 at the age of 15 and moved with him to Gonzales, Texas, in 1831. Susanna's only child, Angelina Elizabeth Dickinson, was born in 1834. When her husband Alamron went off to serve in the Texas cause in October 1835, Susanna joined him in San Antonio, probably in December, and lodged in Ramón Músquiz's home, where she opened her table to boarders (among them David Crockett). On the arrival of Santa Anna's advance guard on February 23, 1836, Almaron hastened Susanna and Angelina into the Alamo on horseback. Thereafter, while she did at times patrol the compound with tins of hot drink for the garrison, Susanna remained, for the most part, sequestered inside of the sacristy of the Alamo church where her only knowledge of the siege was by way of sound. She witnessed none of the battle on March 6th and her only encounter with any of the defenders was when her husband Almaron rushed in to announce, "Great God Sue! The Mexicans are inside our walls! If they spare you, save our child. Then, after a parting kiss, he rushed out with drawn sword into the fray, never to be see alive again by Susanna. Susanna witnessed the death of little Jacob Walker of Nacodoches, an unarmed gunner who'd run suddenly into the Sacristy, seeking a place to hide. It must have been a horrifying sight indeed for her to see Walker raised up by bayonets and then pitched about like fodder. Escorted out of the Church by a kindly Mexican officer, Susanna witnessed the grisly sight of all the carnage in the plaza. She later recallled how she even recognized Davy Crockett, lying dead and mutilated between the church and two story barrack and even noticed his peculiar cap lying neatly by his side. Though slightly wounded in the calf by a stray shot, Susanna and Angelina, along with the other surviving women and children were escorted by the Mexican officer to Músquiz's home. The women were later interviewed by Santa Anna, who gave each a blanket and two dollars in silver before releasing them. Legend says Susanna displayed her husband's Masonic apron to a Mexican general in a plea for help and that Santa Anna offered to take Angelina to Mexico. Santa Anna sent Susanna and her daughter, accompanied by Juan N. Almonte's servant Ben, to Sam Houston with a letter of warning dated March 7. On the way, the pair met Joe, William B. Travis's slave, who had been freed by Santa Anna. The party was discovered by Erastus (Deaf) Smith and Henry Wax Karnes. Smith guided them to Houston in Gonzales. After the tragic events at the Alamo, Susanna lived a long and troubled life, marrying five times and at one low point, even living in a brothel, before achieving a measure of stability and prosperity with her last husband, Joseph William Hannig. Susanna died in Austin. October 7th, 1883. But before she passed, she made at least one visit back to the Alamo to point out locations in the church where she had witnessed the Alamo's final moments. That alone must've been a grave and painful ordeal for her. |

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Jan 24, 2006 10:39:39 GMT -5

This photo of Angelina Dickinson has been mis-identified time and again in history books as being her mother, Susanna Dickinson. This photo of Angelina Dickinson has been mis-identified time and again in history books as being her mother, Susanna Dickinson.Angelina's only claim to fame in the Alamo story is that she was with her mother in the Alamo when it fell. But, at only eighteen months of age, it is hardly likely that she would've, or could've remembered anything---even one of Alamo commander William Barrett Travis' last acts---placing his threaded catseye ring around her neck as a keepsake. Nevertheless, she has been hailed and revered as the "Babe of The Alamo" by sentimental Texans. At the end of the revolution, Angelina and her mother moved to Houston. Between 1837 and 1847 Susanna Dickinson married three times. Angelina and her mother were not, however, left without resources. For their participation in the defense of the Alamo, they received a donation certificate for 640 acres of land in 1839 and a bounty warrant for 1,920 acres of land in Clay County in 1855. In 1849 a resolution by Representative Guy M. Bryanqv for the relief of "the orphan child of the Alamo" to provide funds for Angelina's support and education failed. At the age of seventeen, with her mother's encouragement, Angelina married John Maynard Griffith, a farmer from Montgomery County. Over the next six years, the Griffiths had three children, but the marriage ended in divorce. Leaving two of her children with her mother and one with an uncle, Angelina drifted to New Orleans. Rumors spread of her promiscuity. Before the Civil War she became associated in Galveston with Jim Britton, a railroad man from Tennessee who became a Confederate officer, and to whom she gave Travis's ring. She is believed to have married Oscar Holmes in 1864 and had a fourth child in 1865. Whether she ever married Britton is uncertain, but according to Flake's Daily Bulletin, 35 year old Angelina died in Galveston as "Em Britton" in 1869 of a uterine hemorrhage. |

|

|

|

Post by Bromhead24 on Jan 24, 2006 11:02:15 GMT -5

I read that Susanna could neither read nor write at the time of the Alamo.

|

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Jan 24, 2006 11:56:25 GMT -5

I read that Susanna could neither read nor write at the time of the Alamo. That's true, Bromhead, but at least she could cipher. According to Mrs. D. there were some 8,000 Mexican troops in San Antonio after the Alamo defenders had killed upwards of 1,600 of them! Now, I wonder whose hat those numbers were drawn out of? It couldn't be that she may've been---God forbid--- coaxed! |

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Jan 26, 2006 12:46:40 GMT -5

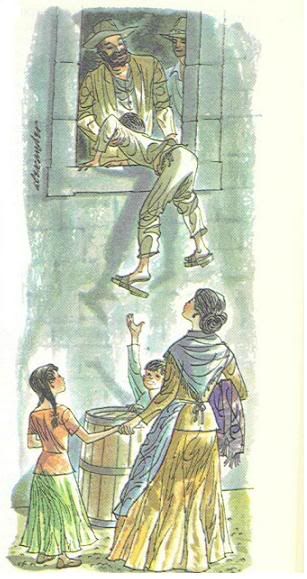

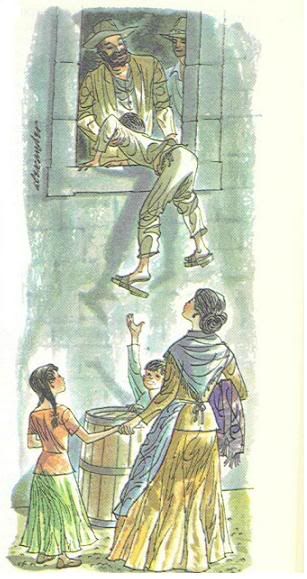

More on Susanna Dickinson : According to the Handbook of Texas History,On May 24, 1829, she (Susanna) married Almaron Dickinson before a justice of the peace in Bolivar, Hardeman County, Tennessee. The couple remained in the vicinity through the end of 1830. The Dickinsons arrived at Gonzales, Texas, on February 20, 1831, in company with fifty-four other settlers, after a trip by schooner from New Orleans. On May 5 Dickinson received a league of land from Green DeWitt, on the San Marcos River in what became Caldwell County. He received ten more lots in and around Gonzales in 1833 and 1834. The Dickinsons lived on a lot just above the town on the San Marcos River, where Susanna took in at least one boarder. A map of Gonzales in 1836 shows a Dickinson and Kimble hat factory in Gonzales. Susanna's only child, Angelina Elizabeth Dickinson, was born on December 14, 1834. Susanna and her daughter may have joined other families hiding in the timber along the Guadalupe River in early October 1835, when Mexican troops from San Antonio demanded the return of an old cannon lent to Gonzales four years earlier. The resulting skirmish, the battle of Gonzales, was the first fight of the Texas Revolution. Susanna said goodbye to her husband on October 13 as the volunteers left for San Antonio under command of Stephen F. Austin. She remained in Gonzales through November, when newly arriving troops looted her home. NOTE: The report of this break-in was documented in a letter from Launcelot Smither. (SEE ALAMO COURIERS) Noncombatants being escorted out of the Alamo, during a reenactment at Alamo Village. In reality, those three boys in the group, much like Anthony Wolf's two sons, would've likely been killed.

|

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Jan 17, 2007 13:31:50 GMT -5

In Enrique Esparza's memoirs, the little boy of the Alamo recollects how his family entered the Alamo through a window---and how he himself had to pass over the top of a cannon, while doing so. There are some who speculate that the sacristy window in question may be the window Enrique was talking about. The fact that Enrique's father, defender Gregorio Esparza, fought a small gun in the church, lends further credence to this claim. I believe that Enrique said how his mother saw his father fall in battle. If Gregorio had been working a small gun in the (east) window of the sacristy where the women and children were sequestered, then this would be a plausible claim. What do you think? |

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Jan 17, 2007 21:58:45 GMT -5

The Story of

Enrique Esparza

As told in The San Antonio Light,

Saturday November 22,1902

Since the death of Senora Candelaria Villanueva, several years ago at the age of 112 there is but one person alive who claims to have been in the siege of the Alamo. That person is Enrique Esparza, now 74 years old, who, firm-stepped, clear-minded and clear-eyed, bids fair to live to the age of the woman who for so long shared honors with him.

Enrique Esparza, who tells one of the most interesting stories ever narrated, works a truck garden on Nogalitos street between the southern Pacific Railroad track and the San Pedro creek. Here he lives with the family of his son, Victor Esparza. Every morning he is up before daybreak and helps load the wagons with garden stuff that is to be taken up town to market.

He is a farmer of experience and contributes very materially to the success of the beautiful five acres garden, of which he is the joint proprietor.

While claims of Enrique Esparza have been known among those familiar with the historical work done by the Daughters of the Republic, an organization which has taken great interest in getting first-hand information of the period of Texas Independence, the old man was not available up to about five years ago, for the reason that he resided on his farm in Atascosa county. This accounts for the fact that he is not well enough known to be included in the itinerary when San Antonians are proudly doing the town with their friends.

Esparza tells a straight story. Although he is a Mexican, his gentleness and unassuming frankness are like the typical odd Texan. Every syllable he speaks to uttered with confidence and in his tale, he frequently makes digressions, going into details of relationship of early families of San Antonio and showing a tenacious memory. At the time of the fight of the Alamo he was 8 years old. His father was a defender, and his father's own brother an assailant of the Alamo. He was a witness of his mother's grief, and had his own grief, at the slaughter in which his father was included. As he narrated to a reporter the events in which he was so deeply concerned, his voice several times choked and he could not proceed for emotion. While he has a fair idea of English, he preferred to talk in Spanish.

"My father, Gregorio Esparza, belonged to Benavides' company, in the American army," said Esparza, "and I think it was in February, 1836, that the company was ordered to Goliad when my father was ordered back alone to San Antonio, for what I don't know. When he got here there were rumors that Santa Ana was on the way here, and many residents sent their families away. One of my father's friends told him that he could have a wagon and team and all necessary provisions for a trip, if he wanted to take his family away. There were six of us besides my father; my mother, whose name was Anita, my eldest sister, myself and three younger brothers, one a baby in arms. I was 8 years old.

"My father decided to take the offer and move the family to San Felipe. Everything was ready, when one morning, Mr. W. Smith, who was godfather to my youngest brother, came to our house on North Flores street, just above where the Presbyterian church now is, and told my mother to tell my father when he came in that Santa Ana had come. (Northeast corner of Houston and N. Flores Streets.)

"When my father came my mother asked him what he would do. You know the Americans had the Alamo, which had been fortified a few months before by General Cos.

"Well, I'm going to the fort" my father said.

"Well, if pop goes, I am going along, and the whole family too.

"It took the whole day to move and an hour before sundown we were inside the fort. Where was a bridge over the river about where Commerce street crosses it, and just as we got to it we could her Santa Anna's drums beating on Milam Square, and just as we were crossing the ditch going into the fort Santa Anna fired his salute on Milam Square.

"There were a few other families who had gone in. A Mrs. Cabury[?] and her sister, a Mrs. Victoriana, and a family of several girls, two of whom I knew afterwards, Mrs. Dickson, Mrs. Juana Melton, a Mexican woman who had married an American, also a woman named Concepcion Losoya and her son, Juan, who was a little older than I.

"The first thing I remember after getting inside the fort was seeing Mrs. Melton making circles on the ground with an umbrella. I had seen very few umbrellas. While I was walking around about dark I went near a man named Fuentes who was talking at a distance with a soldier. When the latter got near me he said to Fuentes:

"Did you know they had cut the water off?"

"The fort was built around a square. The present Hugo-Schmeltzer building is part of it. I remember the main entrance was on the south side of the large enclosure. The quarters were not in the church, but on the south side of the fort, on either side of the entrance, and were part of the convent. There was a ditch of running water back of the church and another along the west side of Alamo Plaza. We couldn't got to the latter ditch as it was under fire and it was the other one that Santa Anna cut off. The next morning after we had gotten in the fort I saw the men drawing water from a well that was in the convent yard. The well was located a little south of the center of the square. I don't know whether it is there now or not.

"On the first night a company of which my father was one went out and captured some prisoners. One of them was a Mexican soldier, and all through the siege, he interpreted the bugle calls on the Mexican side, and in this way the Americans know about the movements of the enemy.

"After the first day there was fighting. The Mexicans had a cannon somewhere near where Dwyer avenue now is, and every fifteen minutes they dropped a shot into the fort.

"The roof of the Alamo had been taken off and the south side filled up with dirt almost to the roof on that side so that there was a slanting embankment up which the Americans could run and take positions. During the fight I saw numbers who were shot in the head as soon as they exposed themselves from the roof. There were holes made in the walls of the fort and the Americans continually shot from these also. We also had two cannon, one at the main entrance and one at the northwest corner of the fort near the post office. The cannon were seldom fired.

"I remember Crockett. He was a tall, slim man, with black whiskers. He was always at the head. The Mexicans called him Don Benito. The Americans said he was Crockett. He would often come to the fire and warm his hands and say a few words to us in the Spanish language. I also remember hearing the names of Travis and Bowie mentioned, but I never saw either of them that I know of.

"After the first few days I remember that a messenger came from somewhere with word that help was coming. The Americans celebrated it by beating the drums and playing on the flute. But after about seven days fighting there was an armistice of three days and during this time Don Benito had conferences every day with Santa Anna. Badio, the interpreter, was a close friend of my father, and I heard him tell my father in the quarters that Santa Anna had offered to let the Americans go with their lives if they would surrender, but the Mexicans would be treated as rebels.

"During the armistice my father told my mother she had better take the children and go, while she could do so safely. But my mother said:

"No!, if you're going to stay, so am I. If they kill one they can kill us all.

"Only one person went out during the armistice, a woman named Trinidad Saucedo.

"Don Benito, or Crockett, as the Americans called him, assembled the men on the last day and told them Santa Anna's terms, but none of them believed that any one who surrendered would get out alive, so they all said as they would have to die any how they would fight it out.

"The fighting began again and continued every day, and nearly every night,. One night there was music in the Mexican camp and the Mexican prisoner said it meant that reinforcements had arrived.

"We then had another messenger who got through the lines, saying that communication had been cut off and the promised reinforcements could not be sent.

"On the last night my father was not out, but he and my mother were sleeping together in headquarters. About 2 o'clock in the morning there was a great shooting and firing at the northwest corner of the fort, and I heard my mother say:

"Gregorio, the soldiers have jumped the wall. The fight's begun.

"He got up and picked up his arms and went into the fight. I never saw him again. My uncle told me afterwards that Santa Anna gave him permission to get my father's body, and that he found it where the thick of the fight had been.

"We could hear the Mexican officers shouting to the men to jump over, and the men were fighting so close that we could hear them strike each other. It was so dark that we couldn't see anything, and the families that were in the quarters just huddled up in the corners. My mother's children were near her. Finally they began shooting through the dark into the room where we were. A boy who was wrapped in a blanket in one corer was hit and killed. The Mexicans fired into the room for at least fifteen minutes. It was a miracle, but none of us children were touched.

"By daybreak the firing had almost stopped, and through the window we could see shadows of men moving around inside the fort. The Mexicans went from room to room looking for an American to kill. While it was still dark a man stepped into the room and pointed his bayonet at my mother's breast, demanding:

"Where's the money the Americans had?"

"If they had any,' said my mother, "you may look for it.'

"Then an officer stepped in and said:

"What are you doing? The women and children are not to be hurt.

"The officer then told my mother to pick out her own family and get her belongings and the other women were given the same instructions. When it was broad day the Mexicans began to remove the dead. There were so many killed that it took several days to carry them away.

"The families, with their baggage, were then sent under guard to the house of Don Ramon Musquiz, which was located where Frank Brothers store now is, on Main Plaza.(Southeast corner of Soledad and Commerce Streets, now a parking lot, 1991). Here we were given coffee and some food, and were told that we would go before the president at 2 o'clock. On our way to the Musquiz house we passed up Commerce street, and it was crowded as far as Presa street with soldiers who did not fire a shot during the battle. Santa Anna had many times more troops than he could use.

"At 3 o'clock we went before Santa Anna. His quarters were in a house which stood where L. Wolfson's store now is.(Middle of Commerce Street, north side, between Main Avenue and Soledad Street). He had a great stack of silver money on a table before him, and a pile of blankets. One by one the women were sent into a side room to make their declaration, and on coming out were given $2 and a blanket. While my mother was waiting her turn Mrs. Melton, who had never recognized my mother as an acquaintance, and who was considered an aristocrat, sent her brother, Juan Losoya, across the room to my mother to ask the favor that nothing be said to the president about her marriage with an American.

"My mother told Juan to tell her not to be afraid.

"Mrs. Dickson was there, also several other woman. After the president had given my mother her $2 and blanket, he told her she was free to go where she liked. We gathered what belongings we could together and went to our cousin's place on North Flores street, where we remained several months."

|

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Oct 27, 2007 11:17:08 GMT -5

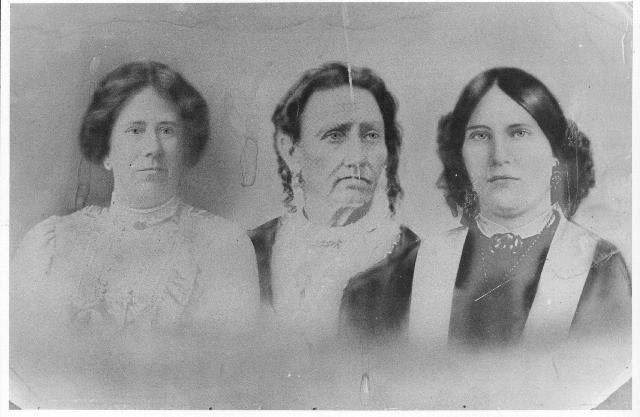

I found this unusual photo on the internet of the Dickinson family. It's merely captioned, "Sally Burns, Granddaughter of Susanna Wilkerson Dickinson, Susanna Wilkerson Dickinson and her daughter, Angelina Elizabeth Dickinson." The granddaughter's got me stumped. Could Susanna's new husband have had children and it is his granddaughter? I don't recall reading anywhere that Susanna had any other children, either than Angelina. What's your take on this conundrum? |

|

|

|

Post by Greg C. on Oct 27, 2007 12:10:37 GMT -5

If Sussanah ever did learn to read and write, its a shame she didnt write a book. That would have been the only true account of the battle.

|

|

|

|

Post by Cole_blooded on Oct 27, 2007 18:05:42 GMT -5

Probably a partial true account of the battle being she was in the Alamo Church/Chapel with her daughter! TED COLE....aka....Cole_blooded  |

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Oct 27, 2007 19:25:13 GMT -5

In the accounts that we do have from Susanna, she seems to be biased against the Mexican women in the Alamo. She says, for instance, that Gertrudis Alsbury left the fort before the assault and reported to Santa Anna the weakened condition of the garrison. In reality, Gertrudis remained in the Alamo and was discovered in one of the rooms in the west wall. The fact that Gertrudis was not sequestered in the sacristy along with the other women and children may've led Susanna to this erroneous conclusion.

|

|

|

|

Post by seguin on Oct 27, 2007 22:08:48 GMT -5

Or just a partial account of the battle from a survivor but not necassarily true all the way!

|

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Oct 28, 2007 13:26:13 GMT -5

Or just a partial account of the battle from a survivor but not necassarily true all the way! It's sort of like the story of The Blind Men And The Elephant: "Though each was partly in the right, All were in the wrong!" |

|

|

|

Post by Greg C. on Nov 15, 2007 17:55:34 GMT -5

Or just a partial account of the battle from a survivor but not necassarily true all the way! It's sort of like the story of The Blind Men And The Elephant: "Though each was partly in the right, All were in the wrong!" That saying sums up quite a lot of things lol... |

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Nov 16, 2007 10:11:01 GMT -5

There's a television commercial about a local car dealership in Kyle, Texas that's owned by one Bill Dickinson. I wonder if there's any relation?

|

|

|

|

Post by Bromhead24 on Nov 16, 2007 12:10:27 GMT -5

In the accounts that we do have from Susanna, she seems to be biased against the Mexican women in the Alamo. She says, for instance, that Gertrudis Alsbury left the fort before the assault and reported to Santa Anna the weakened condition of the garrison. In reality, Gertrudis remained in the Alamo and was discovered in one of the rooms in the west wall. The fact that Gertrudis was not sequestered in the sacristy along with the other women and children may've led Susanna to this erroneous conclusion.   |

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Nov 16, 2007 12:19:53 GMT -5

It must've been a harrowing experience, at any rate. One in which a person's focus is only on those who are currently surrounding her at the time.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bromhead24 on Nov 16, 2007 12:25:34 GMT -5

And for the Mexicans, who in the "Fog of War" restrained their self mostly..

|

|

|

|

Post by neferetus on Nov 16, 2007 12:30:47 GMT -5

You know, the Duke destroyed the south wall of the chapel, just for that scene.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bromhead24 on Nov 16, 2007 13:01:35 GMT -5

You know, the Duke destroyed the south wall of the chapel, just for that scene. Thats too bad, who knows what it might look like today if he had left it intact. |

|